|

Esperanto

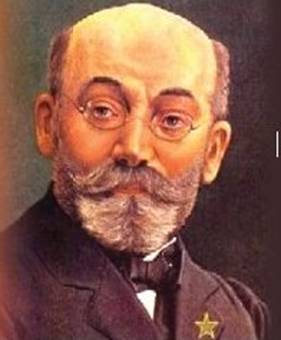

is an artificial language, published in 1887 by Dr L L Zamenhof. Dr Zamenhof,

who was born in 1859, lived his early years in the Polish town of Bialystok -

then part of Russia. At that time the town was split into factions, and, with

a strong Jewish and Islamic population, the various groups, each with its own

language, tended to live very much apart, and there were often clashes

between them. Dr

Zamenhof thought that the problem was the lack of a common language, and he

set out to write a language which could be learned easily as a second

language, without having the problem that exists with national languages, of

imposing one culture onto another. Esperanto would be a ‘neutral’ language. Despite

the problems of two world wars and the Russian Revolution the language has

continued to grow since that time. People such as Tolstoy and Jules Verne

were among the early learners of the language. Today, it is difficult to say

how many Esperantists there are, but obviously the strength is not in

English-speaking countries. There are, perhaps, between one and two thousand

people in the United Kingdom who can speak Esperanto to varying degrees. The

World Esperanto Organisation (Universala Esperanto-Asocio) is based in

Rotterdam. It has, throughout the world, a large number of delegates who

offer help to fellow Esperantists travelling in or through the area in which

they live. A Year Book listing all of the delegate and their locations, is

available to members of UEA. In

Britain there is a national association (Esperanto Association of Britain)

based in Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent. Scotland has a separate association. The

country is dicided into regions and most of these have a federation and

various local groups. The group in Ilford is within the area of the Eastern

Federation, and there are also groups in Southend-on-Sea, Ipswich &

Felixstowe, and Braintree. We

know that English is very much an international language, but it does come

with its own culture. In many areas of the world English has dominated and

destroyed much of the indigenous cultures and languages. It is for this

reason that Esperanto, as a neutral language, is there to protect the native

languages. Almost

every year each country where there is a significant number of Esperantists

willl organise a national Esperanto congress. The British Esperanto Congress

for 2013 is in Ramsgate. On a world scale a global congress (Universala

Kongreso de Esperanto) is organised on a yearly basis, although there were

obviously problems during the two world wars.

The UK for 2013 is in Reykjavik, Iceland. In

some way or another Esperanto has shown itself in all walks of life. One

example is the world of philately. Many countries have issued Esperanto

stamps, especially when a world congress has been arranged in that country,

and there is an Esperanto Philatelic group which is based in Trieste, Italy. People

do not believe that there is such a thing as an Esperanto culture, but there

are many thousands of original works in the language, as well as a wealth of

translations. Recently Clive Boutle has published a bilingual anthology of

Esperanto literature “Star in a Night Sky,” edited by Paul Gubbins. This book

gives an insight into the wealth of Esperanto literature that is in

existence. (See info@francisboutle.co.uk). Britain

is fortunate that it is very close to Europe where there are a large number

of countries and languages. Most of these countries have a national Esperanto

Association and it is very easy and relatively cheap to attend these. In

addition a visit to the centre of the World Esperanto Association in

Rotterdam is also very interesting, especially for the library and the book

shop, which offers not just a large selection of books and magazines, but

also games, learning material and souvenirs. So

we come to the final point..... why learn Esperanto? Well, if you like to

travel and to meet people, the Esperanto world will give you that

opportunity. You meet with people on equal terms, not with one of you

struggling with a foreign language. Esperanto is also a very useful base for

the learning of other, national, languages. Latin was always seen to be

useful in this guise, but is so difficult to learn. Recent research in

Canada, outlined in New Scientist for May 2012 suggests that in the case of

bilingual people, dementia can be delayed by up to four years. Esperanto can

keep your brain active. |

|

WHAT IS ESPERANTO? |

|

KIO ESTAS ESPERANTO? |

|

Hejmpaĝo/Home Page |